Mercury Legacy Products – Hospital Equipment

Dental Amalgam Dispenser

Description:

Prior to the mid-1980s, dentists mixed their own mercury dental amalgam in their clinics. They used dental amalgam dispensers to dispense a proportionally measured amount of liquid mercury combined with silver, tin, and copper, as well as small amounts of other metals, including zinc, indium, or palladium. After mixing, the resulting amalgam was packed into a person’s tooth, creating a filling.

In 1984, the American Dental Association (ADA) recommended that dentists eliminate the use of bulk mercury by switching to pre-encapsulated mercury amalgam alloy in their practices. Measurement of the ratio of liquid mercury to amalgam powder is much more exact with the pre-encapsulated technique. The use of pre-encapsulated dental amalgam eliminated the need for dental amalgam dispensers and they are no longer manufactured or sold in the U.S. Dental amalgam fillings typically contain around 50 percent mercury, which is more than a half gram of mercury.

Purpose of the Mercury:

Dental amalgam dispensers mixed elemental mercury with other powdered metals to create a dental amalgam used in tooth restoration and for filling cavities. Dental amalgam still contains mercury but is currently sold in pre-packaged capsules. Non-mercury alternatives for dental amalgam are made of resin and composite materials, including glass ionomer cement, gold foil, gold alloy, and metal and ceramic dental fillings and crowns.

Potential Hazards:

Dental amalgam dispensers can leak or malfunction causing a mercury release. Spills from bulk elemental mercury that is stored on-site would present a significant risk of exposure as well as extensive cleanup costs. However, bulk elemental mercury would most likely only be found in dental offices that have been in operation since the early 1980s and that still have this older equipment on site. Most dentists have removed these devices and their jars of bulk mercury.

Spills greater than one pound of elemental mercury (about two tablespoons) must be reported to the appropriate state environmental agency. If a leak or break occurs, persons should immediately contact their state environmental agency for instructions on proper clean-up and disposal. Persons that have been exposed to a mercury spill should also contact the public health department or poison control center.

Recycling/Disposal:

Out-of-use dental amalgam dispensers must be disposed of as a hazardous waste at a licensed hazardous waste facility – they are considered “contact amalgam waste” because of possible mercury contamination. Any mercury remaining in the device, as well as any bulk elemental mercury that is still stored at the dental clinic, should be sent to a mercury recycler for reclamation.

Statutes and Other Information: Historically, dentists mixed dental amalgam on-site using bulk elemental mercury and metal powders. Today, dental amalgam is purchased in pre-dosed amalgam capsules; therefore, the need for dental amalgam dispensers is obsolete.

Dental amalgam waste, including the pre-encapsulated amalgam can be recycled through an ADA-approved amalgam recycler. Mercury-containing medical waste such as dental amalgam is banned from solid waste disposal and must be recycled or managed as a hazardous waste.

Related Links:

https://www.epa.gov/mercury/mercury-dental-amalgam

Esophageal Dilators (Bougies)

Description:

An esophageal dilator, also referred to as a bougie tube, is used to dilate the esophagus of a patient in response to medical conditions or treatments that cause esophageal narrowing or tissue shrinkage.

The dilator is a long, flexible tube that is slipped down the patient’s throat into the esophagus, where it remains in place for several minutes before it is extracted. Older esophageal dilators consist of thick latex-coated tubing with approximately 2-3 pounds (more than 1,000 grams) of elemental mercury at the bottom of the tube.

Purpose of the Mercury:

The mercury in esophageal dilators is used as a weight at the bottom of the tube. The density and liquid properties of mercury make it ideal to use as a flexible weight, necessary to insert the tube into the patient’s constricted esophagus.

Potential Hazards:

Over time, the latex covering of the esophageal dilator tubing can become brittle and cracked, which may lead to a mercury release. Older mercury-containing esophageal dilators have been known to rupture during handling or use causing potential environmental, patient, and employee hazards. This is the reason that mercury-containing esophageal dilators have an expiration date.

The large amount of mercury contained in esophageal dilators would present a significant risk of exposure as well as extensive cleanup costs if spilled. Spills greater than one pound of elemental mercury (about two tablespoons) must be reported to the appropriate state environmental agency. If a leak or break occurs, persons should immediately contact their state environmental agency for instructions on proper clean-up and disposal. Persons that have been exposed to a mercury spill should also contact the public health department or poison control center.

Recycling/Disposal:

Out-of-service mercury-containing medical devices must be disposed of as hazardous waste through a licensed hazardous waste facility. The mercury collected from the esophageal tubes should be sent to a reclamation facility and recycled.

Statutes and Other Information:

The amount of mercury contained in esophageal dilators and bougie tubes makes these products subject to sales restrictions in certain states, including Connecticut, Louisiana, and Rhode Island. Esophageal dilators are also subject to sales restrictions in other states, including California, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, and Vermont. These states do allow manufacturers to apply for an exemption, which, if approved, would allow them to sell these products in the state after the effective phase-out date.

Mercury-filled esophageal dilators and bougie tubes are becoming rare, and research has not identified any companies that still manufacture these devices. Instead, water- and tungsten-filled dilators are now commonly used.

Related Links:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3770987/

https://www3.epa.gov/region9/waste/p2/projects/hospital/mercury.pdf

Feeding Tubes

Description:

A feeding tube is a medical device used to provide nutrition to patients that cannot obtain nutrition by swallowing. They are used to administer food or drugs. The most common feeding tube is the nasogastric tube, which is passed through a patient’s nose, past the throat, and into the stomach. The tubes are usually made of polyurethane and silicone. Older tubes can contain a small amount of mercury as a weight at the bottom of the tube, which helps guide the tube into place.

Purpose of the Mercury:

The weight of the mercury guides the tube into place using gravity.

Potential Hazards:

The polyurethane coating of a feeding tube is not easily broken during normal handling. However, if a leak or break occurs, persons should immediately contact their state environmental agency for instructions on proper clean-up and disposal. Persons that have been exposed to a mercury spill should contact the public health department or poison control center.

Recycling/Disposal:

Out-of-service mercury-containing medical devices must be disposed of as hazardous waste through a licensed hazardous waste facility. The mercury collected from the feeding tubes should be sent to a reclamation facility and recycled.

Statutes and Other Information:

The amount of mercury contained in weighted feeding tubes (greater than one gram) would make these products subject to sales restrictions in certain states, including Connecticut, Louisiana, and Rhode Island.

Weighted feeding tubes are no longer common and the few that are currently manufactured and sold in U.S. do not contain mercury – they use tungsten as a weight.

Gastrointestinal Tubes

Description:

A gastrointestinal tube is used to eliminate intestinal obstructions. Types of gastrointestinal tubes include Miller Abbott, Blakemore, and Cantor tubes. The tube is passed down a patient’s esophagus, through the stomach, and into the small intestine to help remove or reduce intestinal obstructions. Historically, these tubes had a balloon containing mercury as the flexible weight, which would help guide the tube into place. When filled to capacity, these devices contained approximately 2 pounds (1,000 grams) of mercury.

Purpose of the Mercury:

The weight of the mercury guides the tube into place using gravity.

Potential Hazards:

The large amount of mercury contained in gastrointestinal tubes would present a significant risk of exposure as well as extensive cleanup costs if spilled. Spills greater than one pound of elemental mercury (about two tablespoons) must be reported to the appropriate state environmental agency. If a leak or break occurs, persons should immediately contact their state environmental agency for instructions on proper clean-up and disposal. Persons that have been exposed to a mercury spill should contact their public health department or poison control center.

Recycling/Disposal:

Out-of-service mercury-containing medical devices must be disposed of as hazardous waste through a licensed hazardous waste facility. The mercury collected from the gastrointestinal tubes should be sent to a reclamation facility and recycled.

Statutes and Other Information:

The amount of mercury contained in gastrointestinal tubes (greater than one gram) would make these products subject to sales restrictions in certain states, including Connecticut, Louisiana, and Rhode Island.

Gastrointestinal tubes filled with mercury are no longer widely used in the medical industry and no manufacturers of mercury-containing gastrointestinal tubes have been identified. New gastrointestinal tubes are manufactured and sold un-weighted (i.e., the hospital must supply their own weight, such as sterile water) or with tungsten gel as the weight.

Intraocular Pressure Devices

Description:

Small bags of mercury were historically used as weights to apply pressure to the eye prior to cataract surgery. These mercury-filled balloons, which were the size of a small egg, contained approximately 175 grams of elemental mercury that was double or triple bagged and placed on the patient’s eye prior to surgery.

Purpose of the Mercury:

When placed on the eye, the weight of the mercury on the eyeball kept fluid from accumulating at the normal rate, softening the eyeball prior to surgery. This practice reduced the pressure within the eyeball, simplifying surgery. However, this method is no longer used.

Note: as the need for these devices decreased, they were often shoved to the back of cabinets or drawers and forgotten about. Therefore, some effort must be exerted to search for these unused items and to properly dispose of them.

Potential Hazards:

These mercury-filled balloons can be easily broken or ruptured – especially as they get older and the integrity of the rubber balloon degrades. If a leak or break occurs, persons should immediately contact their state environmental agency for instructions on proper clean-up and disposal. Persons that have been exposed to a mercury spill should contact the public health department or poison control center.

Recycling/Disposal:

Out-of-service mercury-containing medical devices must be disposed of as hazardous waste through a licensed hazardous waste facility. The mercury-filled intraocular pressure devices should be sent to a reclamation facility and recycled.

Statutes and Other Information:

Intraocular mercury pressure reducers are no longer commercially available, and the practice of weighting the eye is largely obsolete. New techniques and less invasive tools for surgery mean that pressure reduction is not always necessary, and the practice of weighting the eye prior to cataract surgery is less common.

Strain Gauge

Description:

A strain gauge is a sensor attached to a plethysmograph, which measures arterial blood flow. The strain gauge consists of elemental mercury contained in a fine rubber tube, which is placed around a patient’s limb or digit (e.g., forearm, leg, calve, finger, or toe). A standard limb-style mercury strain gauge contains approximately 1.25 grams of elemental mercury. Pressure is applied to the patient’s limb and the increase in its circumference is measured. This measurement indicates changes in blood flow and is used to measure blood pressure and check for blood clots. The technique is called strain gauge plethysmography.

Purpose of the Mercury:

The mercury is contained in a silastic rubber tube. Swelling of the body part results in stretching of the tube, making it both longer and thinner, which increases electrical resistance. The mercury is used as a measuring element for this electrical continuity.

Potential Hazards:

Strain gauges seldom break during normal handling and use. However, if a leak or break occurs, persons should immediately contact their state environmental agency for instructions on proper clean-up and disposal. Persons that have been exposed to a mercury spill should contact the public health department or poison control center.

Recycling/Disposal:

Out-of-service mercury-containing medical devices must be disposed of as hazardous waste through a licensed hazardous waste facility. The mercury collected from the strain gauges should be sent to a reclamation facility and recycled.

As a gauge ages, the copper electrodes at the ends are dissolved into the mercury. It appears as a darkening of the mercury, which begins at the end of the gauge and progresses toward to middle. This process causes the pressure in the gauge to go down, and eventually the gauge will lose electrical continuity when it is stretched too far. If this happens, the strain gauge will no longer work. Mercury strain gauges that no longer function may be returned to their manufacturer for recycling.

Statutes and Other Information:

The amount of mercury contained in strain gauges (greater than one gram) makes these products subject to sales restrictions in certain states, including Connecticut, Louisiana, and Rhode Island.

Mercury-filled strain gauges are no longer common and are rarely used. Only one company has informed the IMERC-member states that they manufacture mercury strain gauges. This company, D.E. Hokanson, Inc. (hyperlink to database details), reported to the IMERC-member states during the 2001 and 2004 triennial reporting periods on their mercury strain gauges, but has not yet reported 2007 data. It is uncertain whether this company continues to manufacture mercury strain gauges; however they are listed on the company’s website. Non-mercury alternatives include indium-gallium strain gauges.

Related Links:

http://www.deh-inc.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=faq&faqcategoryid=8

Urinometer

Description:

A urinometer was an instrument used to measure the specific gravity of urine. It was a glass device with a mercury-weighted bulb and an air-filled stem with graduated scale above. Urinometers are basically small hydrometers with a relatively small amount of mercury – less than one gram. When the urinometer is placed in liquid, the float displaces a certain weight and the level to which it sinks is a measure of specific gravity. Specific gravity is the ratio of the density of a given substance to the density of water.

Purpose of the Mercury:

Mercury may be contained in the bulb of the urinometer. The mercury acts as a weight, which makes the urinometer float upright in the liquid urine. The point on the scale, which is in line with the upper level of urine, represents the specific gravity. In a urinalysis, the specific gravity is used to indicate the general functioning of the kidneys, including the kidney’s ability to reabsorb water and chemicals.

Potential Hazards:

Urinometers are usually made of glass, making a mercury urinometer susceptible to breakage. If a leak or break occurs, persons should immediately contact their state environmental agency for instructions on proper clean-up and disposal. Persons that have been exposed to a mercury spill should contact the public health department or poison control center.

Recycling/Disposal:

Out-of-service mercury-containing medical devices must be disposed of as hazardous waste through a licensed hazardous waste facility. The mercury collected from the urinometer will be sent to a mercury recycler for reclamation.

Statutes and Other Information:

Urinometers were used for measuring the specific gravity of urine before more sophisticated technological means were introduced. They required a large volume of urine and additional corrective calculations based on temperature, glucose, and protein. They are rarely used today, and research indicates that new mercury urinometers are no longer produced or available for sale. Today, the most common method used in hospitals and health care facilities to measure specific gravity in a urinalysis is to use urine dipsticks.

Related Links:

http://www.austincc.edu/kotrla/UALect2PhysicalProperties.pdf

X-Ray Machines

Description:

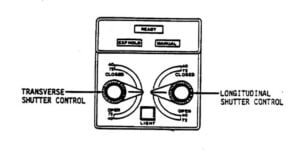

X-ray machines can contain small mercury leveling switches as part of the positive beam limitation (PBL) system, also referred to as the automatic collimation system, which is mounted on the x-ray tube housing. Collimation refers to the process of adjusting an optical instrument (i.e., x-ray machine) to ensure the best possible image quality. The PBL system is an automatic collimation system used in stationary radiographic equipment. The mercury switches in this system usually account for approximately 3-4 grams of mercury per machine, although some may contain significantly more. For example, the Department of Health Services in California encountered an x-ray machine with almost eight grams of mercury when they completed a hospital mercury assessment.

Purpose of the Mercury:

A positive beam limitation system (PBL) uses four miniature mercury switches to assure perpendicularity between the x-ray beam and the film and maintain precise control over the radiation beam.

Potential Hazards: As long as the system remains intact, there is a low probability that there would be a mercury release from this device.

However, x-ray machines may contain other sources of mercury in the x-ray film and chemical processing solutions (e.g., fixer). Therefore, care should be taken whenever handling this equipment to prevent a mercury release.

Recycling/Disposal:

The PBL system, or collimator, should be removed from the x-ray machine for proper disposal. It is relatively easy to remove and there is no major disassembly needed. Out-of-service mercury-containing medical devices must be disposed of as hazardous waste through a licensed hazardous waste facility. A professional service technician will be able to safely remove the mercury switches from the equipment and send them to a mercury reclamation facility for recycling.

It is also important to note that since the PBL collimator system contains lead, the entire device should be disposed of as hazardous waste.

Statutes and Other Information:

In many states, including California, Connecticut, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont, mercury switches are among the list of mercury-added products that are prohibited for sale – whether they are sold alone or as components of another product. These states however, do allow manufacturers to apply for an exemption, which, if approved, would allow them to sell these products in the state after the effective phase-out date.

Previously, Federal Regulation 21 CFR Part 1020 required automatic beam leveler switches to be present in virtually all x-ray machines. However, the PBL system is no longer required by federal regulations and existing systems may be overridden by the operator. These systems may simply be removed and do not need to be replaced. Persons should first review the state regulations to determine if PBL collimator systems are still required by their State Department of Health.

Related Links:

http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=1020&showFR=1

http://www.dtsc.ca.gov/PollutionPrevention/upload/guide-to-mercury-assessment-in-healthcare-facilities.pdf

General References

The links below are general references that provide information pertaining to all mercury-containing products found in hospitals and health care facilities:

General Information about Mercury-Containing Medical Devices:

http://www.dtsc.ca.gov/PollutionPrevention/upload/guide-to-mercury-assessment-in-healthcare-facilities.pdf

http://www.sustainableproduction.org/downloads/An%20Investigation%20Hg.pdf

http://www.hazwastehelp.org/mercury/mercury-medical.aspx

Additional Mercury-Added Devices Found in Hospitals: [NEWMOA Sphygmomanometer]

Hospital Mercury Education and Reduction Programs:

http://www.noharm.org/us_canada/issues/toxins/mercury

Mercury Product Phase-outs, Sales Prohibitions, and Exemptions:

[NEWMOA Ban & Phase-out]

Spill Clean-up Guidance:

http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/massdep/toxics/sources/cleaning-up-elemental-mercury-spills.html